Frank Lloyd Wright: Symbolism and World Making

Frank Lloyd Wright. Unity Temple main sanctuary space. Chicago, IL. 1905

Click here to read in PDF format.

Discussion of the work of Frank Lloyd Wright often falls into either an homage to the cult of personality veiled behind artistic genius or to the more superficial reciting of the physical aspects seen in his “style” of architecture (flat roofs, corner windows, horizontal disposition, etc.). Wright’s idea of “Organic Architecture” was often spoken about both by him and many since him, but the term itself conceals as much as it reveals. In fact, we might ask whether organic architecture was the primary art- system he created, or if there was something underlying the standard tenets of organic architecture that might better explain the process and method by which he lived and worked.

The premise to this essay is that an examination of Wright’s thought and work within the philosophical framework of symbolic forms as espoused by Nelson Goodman will be more useful in providing understanding into the idea of organic architecture as he conceived of and practiced it. Of the philosophers who have addressed the concept of worldmaking, Nelson Goodman is one of the better examples from twentieth century analytic philosophy that wrote concerning this concept in his book Ways of Worldmaking, along with various other writings. Additionally, work from Ernst Cassirer, Susan Langer, Rudolph Arnheim and others will supplement this analysis.

Before we address Wright’s early influences in the development of his process of world making, we will briefly examine Goodman’s worldmaking theory. Nelson Goodman (1906-1998) was an important figure in twentieth century philosophy with contributions in aesthetics, applied logic, metaphysics, epistemology, and philosophy of science. His idea of worldmaking began before his book Ways of Worldmaking (1978) was written with his statement of the “general problem of projection” whereby we project predicates onto reality (a reality that is itself “constructed” by those projections.)

Goodman believed that worlds were made rather than found. And these are made by the construction of world versions, or symbol systems that supply structure. Because any two items are alike in some respects and different in others, it is not defined when something should be classified as being of the same class or two different classes. The criteria needed to be applied to determine this is not found in nature and is supplied by applying a scheme or system of classification. One system is not right or wrong necessarily but a world version must be consistent within itself to be acceptable. “Consistency, coherence, suitability for a purpose, accord with best practice are restraints that Goodman recognizes.” Additionally, in regards to perception, Goodman states that there is “no perception without conception”, nor, after Gombrich, is there an “innocent eye.” Thus, to Goodman, perception is not a neutral activity but how we see is both affected by our world version and our worldmaking can be influenced by our perceptions.

Robert Schwartz, in his essay, “The Power of Pictures,” presents the example of Picasso’s portrait of Gertrude Stein of which it was said that Picasso claimed it would be seen to be an accurate representation of Gertrude even if in the beginning it was thought to look nothing like her. Schwartz uses this to illustrate his main point that pictures “may not only shape our perception of the world; they can and do play an important role in making it.” The power of the picture to emphasize and discriminate certain aspects of the visual object can serve to change the way we see the world. Early in Wright’s career, he discovered Japanese art, and in particular the woodblock print (ukiyo-e). Like Picasso’s portrait of Stein, the Japanese print discriminated in its portrayal of people and nature in a way that produced its particularly elegant, stylized, and idealized formalism. This had a powerful effect not only on Wright’s renderings, but also on his theory of architecture.

One could outline the development of Wright’s worldmaking as follows:

1.) Wright first saw and interpreted art and architecture in a certain way before developing his own system. As Goodman declares in Ways of Worldmaking, “Worldmaking as we know it always starts from worlds already on hand: the making is a remaking.”World systems are not created out of nothing. Perception itself, in Goodman’s view, is a form of worldmaking. Although there are other influences upon Wright worth consideration such as the Froebel block system, the influence I will examine in this paper will be Wright’s exposure to Japanese art; the Japanese print had impressed upon Wright a particular way of seeing the world that appealed to him, so much so that he wrote a book about it.

2.) Wright created a theory and body of work according to the world version he saw, thus expanding and reinforcing his world making system. As he worked with the particulars and grammar of a certain architecture, he would continue to revise and refine it, creating yet additional expressions of his architectural oeuvre over a period of some 70 years. Due to his long and productive career, we can see in Wright’s work phases that were derivative of earlier phases, and also influenced by external forces.

3.) Wright’s worldmaking system(s), along with the skill with which it was conveyed both in architectural works as well as renderings, writings, and persona, has consequently had a strong influence on others whose perceptions of architecture have been influenced by the symbolic values that Wright expressed in his works. Wright’s influence was to affect others to see the world through the lens and world system he created.

As we discuss this symbolic system that Wright created, it should be noted here that Nelson Goodman’s concern was not with endowing symbol systems with meaning or value but rather in outlining a logical structural system, in effect providing a framework much like empty “containers” by which individual worldmakers such as Wright could ‘fill’ value and meaning content into that which was significant to their work. Throughout Wright’s career and writings we see an emphasis on the value content of his symbol system that would not have concerned Goodman and yet became instrumental in the expression of his architecture. Goodman’s symbolic symbol system can be viewed as a new organizing structure with which to gain additional perspective to Wright’s works. It should also be mentioned that even though Wright himself wrote about the symbolic function of form, he did not develop a theoretical structure to his use of symbolic forms as Nelson Goodman had.

PART ONE: GOODMAN’S CONCEPT OF WORLD MAKING DESCRIBED

In the opening chapter to his book, Ways of Worldmaking, Goodman reflects on one of the major themes of Ernst Cassirer’s work as being “Countless worlds made from nothing by use of symbols...” and relates his commonality with Cassirer as including “the multiplicity of worlds, the speciousness of the given, the creative power of the understanding, [and] the variety and formative function of symbols.”7 In defining what is meant by possible worlds, he emphasizes that he is not talking about possible alternate worlds but of multiple actual worlds. Also worth noting is his view on the frame of reference and its role in world making. The two statements, “the sun always moves,” and “the sun never moves” might give one the impression that two different worlds delineated by separate frames of reference resolve these apparent contradictory truths. However, Goodman asks the more foundational question of how one would describe a world without any frame of reference? Our universe, he says, “consists of these ways rather than of a world or of worlds.”

In reference to right versions of worlds we are not to look for a unity underneath these versions but rather in an overall organization embracing them. For Goodman this is “an analytic study of the types and functions of symbols and symbol systems.” He then states what many others, have already stated, that there is no perception without conception, no innocent eye, and no substance as substratum. “We can have words without a world but no world without words or other symbols.” Or in the words of Remei Capdevila-Werning, “Architects contribute to the process of worldmaking not simply in the physical sense of making bricks, but most importantly in a metaphysical one, by creating symbols and symbol systems that further constitute worlds.” And also that, “Any discipline that contributes to the advancement of understanding through symbol systems, such as architecture, contributes also to the creation of a world: the ways of creating meaning are also, in Goodman’s terminology, ways of worldmaking.”

Frank Lloyd Wright as a worldmaker did so using an aesthetic with a highly developed symbol system that expressed his architectural world vision. According to Susan Langer, the primary function of art is to “objectify feeling so that we can contemplate and understand it.”14 By examining Wright’s symbol system we can better understand the Idea he was expressing through his architecture.

Specifically, regarding ways of worldmaking, Goodman delineates five processes that may be used in worldmaking: 1. Composition and decomposition, 2. Weighting, 3. Ordering, 4. Deletion and Supplementation, and 5. Deformation. Composition and decomposition in Goodman’s view involves taking apart and putting together, of dividing wholes into parts, of drawing distinctions, of composing wholes and combining features into more complex assemblies. In this category Goodman includes identification into classes and kinds. For weighting, Goodman says that emphasis and accent and sorting into relevant and irrelevant make up world versions. Ordering can involve temporality as well as proximity and are not “found in the world but are built into a world.” In the category of deletion and supplementation, Goodman includes perceptual exclusion and the idea that we find what we are prepared to find. Lastly, deformation or reshaping may create variations that amount to revelations.

PART TWO: THE EARLY INFLUENCES ON THE DEVELOPMENT OF WRIGHT’S WORLD VERSION

In order to maintain his persona of an original creative genius, Wright notoriously gave little credit for his influence from other sources, primarily only giving credit to his mentor Louis Sullivan and Japanese art. However, even his holding onto the idea of the creative genius can be seen as an influence of Hegelian thought, along with the romanticism of his age. As we consider this in light of Wright’s worldmaking activities, Nelson Goodman says that it is not possible to create from nothing but that to make a world is always to remake one: “Worldmaking begins with one version and ends with another.” And as Capdevila-Werning further points out, “world making is a never-ending and open-ended process, for a version or an interpretation of the world is always susceptible of being modified: its symbolic functioning can reorganize, point out, or bring to the background the constitutive elements of a version without ever reaching an ultimate world and without knowing what the next world will look like.” The artist or architect’s body of work is a succession of phases, adaptations, reformulations, and progression from their early work which often begins under the mentorship of someone else’s style or a currently known style and moves toward a style that begins to bring out their own personal signature and eventually into a mature style that stands distinct and unique in the world--that is, if one is so talented and skillful to achieve this level of mastery of their craft and art.

Wright was such an architect. From his apprenticeship first with Joseph Silsbee and then with Louis Sullivan, Wright began as a “pencil in the master’s hand” beautifully absorbing Sullivan’s flowing ornamentation style as we see in Adler and Sullivan’s Auditorium building in Chicago. Eventually Wright began to distinguish himself from Sullivan by abstracting and geometrizing his ornament rather than drawing in the more literal decoration of his mentor. There were other characteristics to Wright’s work as well that he slowly developed in the decade just before and after 1900 such as his conception of space, the use of materials, and his idea of organic integration, not just of the ornamental aspects of a building but of the entire conception of the building itself. And at this point in his career we have the golden age of his Prairie Style. This alone would have been enough to secure his position as a great architect; however, he went on to develop other styles such as his Usonian, textile block, along with individual masterpieces such as Fallingwater, the Guggenheim and Johnson Wax buildings.

4. Frank Lloyd Wright, Johnson Wax Administration Building Exterior, Racine, WI. 1937.

Even in his diverse output, however, we can see a relationship of one style to another. His Usonian ‘world-version’ would not have arisen without first his Prairie period. The Johnson Wax administration building would not have been what it is without first the Unity Temple and Larkin building. The Johnson Wax administration building can be considered a deformation and recombination of the parti of Unity Temple, a worldmaking activity whereby each new creative work didn’t rise spontaneously from nothing but involved one of Goodman’s worldmaking processes described above in the actualization of Wright’s new work.

Besides Louis Sullivan, the strongest influence on Wright’s work that would remain throughout his career was Japanese art. Wright was not only interested in the Japanese Ho-o-den at the 1893 World’s fair in Chicago because it was a clear contrast from the European Beaux Arts classicism in the rest of the exposition, but he had earlier connections to Japanese influence through Fenollosa and others from his earliest years in Chicago as has been well documented in Kevin Nute’s book, Frank Lloyd Wright and Japan. In fact Fenollosa, the Harvard trained envoy to Japan who helped Japan re- appreciate their heritage of native art, lectured widely in the United States on the aesthetic principles of Japanese art which he believed could be the basis of a new American art and create a synthesis of East and West without the imitation of traditional European styles.19 Wright himself gives an interesting ‘confession’ of his influence from Japan: “Many people have wondered about an Oriental quality they see in my work. I suppose it is true that when we speak of organic architecture, we are speaking of something that is more Oriental than Western. The answer is: my work is, in that deeper philosophical sense, Oriental.”20 A case could be made, although beyond the scope of this paper, that Wright actualized the ideal that Fenollosa sought in his theory of synthesizing the east and the west. The consequent reformation resulting from such a synthesis is again a form of worldmaking on a high level.

That Wright saw something in the Japanese print that influenced his thought becomes very clear in light of his work and writings on the subject. In fact, Wright said of the Japanese print that it was “something upon which a whole philosophy of art might be constructed.”21 Wright said a whole philosophy of art could be derived from the Japanese print, and he in fact wrote a book, The Japanese Print Interpreted, which essentially was foundational to the formulation of his theory of organic architecture. What substance can we derive from such a statement of his and was it mere hyperbole? In Robert Schwartz’s essay “The Power of Pictures,” he says that “...pictures may not only shape our perception of the world; they can and do play an important role in making it.”22 He continues in a line of reasoning very much like Goodman’s idea of worldmaking when stating that “...in devising representations we partake in “world-making,’ that the alternative idea of a world ready-made, waiting out there to be captured in word or image is itself not a viable position. What we see is in part a function of what we look for and pictures can inform our habits of looking.”23 This could not be truer in the case of Wright. When speaking of Edo period Japanese woodblock prints, Oscar Wilde said that they lied about everything and that if one actually traveled to Japan to see what was portrayed in those prints that they would not find it. However, Wright who saw the prints before he first traveled to Japan in 1905 had a different experience. In his autobiography Wright recounts his experience visiting Tokyo (Yedo) with romantic language as he described the city as:

A capital of seven hills, every hill crowned by gay temples and the highways leading over the hills or to them were hung with red paper lanterns....Japanese children seem to always have the right of way; they are gaily dressed as flowers in the sun....Mystery is everywhere...there is brooding quiet over all as though some enchantment wrought an unnatural scene. The sliding paper closure of the openings is usually protected by vertical wooden slats in so many clever geometrical patterns. ..Charming silhouettes are all the time flickering on them, the play to and fro made as human figures pass. The plaintive twang of Samisen strings plucked by a broad ivory blade in the hands of the shopkeeper’s daughter—Hirani-san or Nobu-san— maybe, is heard coming into the glowing unnaturally quiet scene. Yes, it all looks—just like the prints! It does.”

It would seem more probable that Wright when actually stepping foot in Japan some 60 to 100 years after the prints he loved were made would see that it was not at all like the prints; nevertheless, what he saw was a function of what he was looking for and those prints informed his habit of looking, to use Schwartz’s words above. Furthermore, his trained artistic eye would be all the more able to cull out of his perception of the city the extraneous clutter and dissonant artifacts in order to distill to the essential symbolic content of what he had seen in the prints. Goodman says something similar when stating, “we find what we are prepared to find (what we look for or what forcefully affronts our expectations), and that we are likely to be blind to what neither helps nor hinders our pursuits.”25

PART THREE: WRIGHT’S HEGELIAN IDEALISM SEEN IN THE LIGHT OF SYMBOLIC FORMS

In this section I would like to relate Wright’s theory to Hegel’s idealism and both as a way of symbolic forms. Kevin Nute’s research seems to indicate that Wright was familiar with Hegel’s ideas via associations with those who were strong proponents of Hegel’s idealism and probably more specifically with the book, Hegel’s Aesthetics, by John Kedney, published in 1885.26 If, according to Goodman, world versions are not created out of nothing but are remade out of existing versions, what was the nature of that world version that Wright chose to draw from? From the Japanese print Wright saw the idea of the “elimination of the insignificant” expressed most clearly. He did not see this in Western art, or at least he did not approve of the European schools of modernism. Wright was not drawn to simplicity for the sake of minimalism. When he wrote the phrase “the elimination of the insignificant,” the simplifying process was in order to remove the clutter and the accidental in order that the underlying Idea would be expressed. This was not only Japanese in nature but also Hegelian. As Wright wrote to his friend the landscape architect Jens Jensen, “You are a realistic landscapist. I am an abstractionist seeking the pattern behind the realism—the interior structure instead of the comparatively superficial exterior effects you delight in.”27 And Wright also says, “Using this word Nature in the Japanese sense I do not mean that outward aspect which strikes the eye as a visual image of a scene strikes the ground glass of a camera, but that inner harmony which penetrates the outward form or letter, and is its determining character that quality in the thing that is its significance and its Life for us—what Plato calls the “eternal idea of the thing.’28

This correlates closely with Hegel’s aesthetics as Curtis Carter writes:

Art does not, qua art, imitate nature, according to Hegel. Rather, it fuses natural materials with feeling and thought, appropriating shapes, colors, and movements to it own ends. Art

may appear to speak the language of nature just because it appropriates existing natural materials and forms, but art is art only in so far as colors, shapes, and movements are used to express a spiritual content that is merely foreshadowed in natural materials.

... the highest role played by aesthetic symbols in Hegel's view is the expression of spiritual content.

And so, the problem with realism in art, to Wright, was that it was lacking in expressing any spiritual content, or the Idea, as he would often say. And to put it in a more contemporary terminology, we could say that the literal imitation lacked symbolic content of any higher level than the mere visual sense data. The work itself, in physical form, would be the carrier for symbolic content that conveyed the thought and spirit of the artist or architect. Again, Carter gives us a good analogy of this relationship in the human body:

The human body, which incorporates certain spiritual properties in a material form, is a useful model for understanding the mixture of corporeality

and spirit in art. As interior ideas and feelings exteriorize

themselves in facial expression, gesture, or movement, the body

literally expresses certain properties of spirit. This expressive power of the body is analogous to the expressive power which attaches

to aesthetic symbols when they have resulted from an artistic fusion of sensuous materials and the properties of spirit.

Aesthetic symbols display spirit in the material sensuous forms provided by artistic media such as architecture, sculpture, painting, music, and poetry. In so doing they vividly bring to our minds the deepest spiritual interests of mankind-the aesthetic symbols created in these artistic media enable absolute spirit to penetrate the world of nature.

Wright himself didn’t develop a theory of symbolic forms, but there is an interesting section in his book, The Japanese Print, in which he makes reference to the symbolic: “But there is a psychic correlation between the geometry of form and our associated ideas which constitutes its symbolic value. There resides always a certain spell power in any geometric form, which seems more or less a mystery, and is, as we say, the soul of the thing. ...The reason why certain geometric forms have come to symbolize for us and potently to suggest certain human ideas, moods and sentiments—as for instance: the circle, infinity: the triangle, structural integrity, the spire, aspiration; the spiral, organic progress; the square, integrity. It is nevertheless a fact that more or less clearly in the subtle differentiations of these elemental geometric forms, we do sense a certain psychic quality which we may call the ‘spell-power’ of the form, and with which the artist freely plays, as much at home with it as the musician at his keyboard with his notes.”31

Wright further explained regarding the Japanese artist that by his grasp “of geometric form and sense of its symbol-value he has the secret of getting to the hidden core of reality. However fantastic his imaginative world may be it competes with the actual and subdues it by superior loveliness and human meaning.”32 The words “spell power” and “psychic quality” used by Wright seem odd to us now and seem to be used as a placeholder for something he cannot define. However, he seems to be trying to state something similar to Hegel’s idea of the spirit animating sensuous form, to say that there is some animating force beneath the external material nature. Wright seems to be saying, at least in part, that the architect who bases his form on an inner geometric structure, just as he says the Japanese artist does, will be able to grasp the underlying core of reality and also give symbolic power to the physical expression thus created. As Wright states above, he feels that geometric primitives carry symbolic meaning and by using these geometries intentionally he can express in his architecture certain feelings or thoughts. By using the square, for example, the architect can express “integrity.” Possibly Wright hadn’t considered the multivalent nature of symbols and the difficulty of associating a one-to-one correspondence of meaning to form. Even so, however incorrect or incomplete he was in his idea of symbolism, our goal here is to see how Wright expressed his particular version of a symbol system in his own way of worldmaking. Goodman’s system of symbols is not concerned, in any case, with the value content Wright chose to put into his world version. One system is not right or wrong necessarily but a world version must be consistent within itself to be acceptable. “Consistency, coherence, suitability for a purpose, accord with best practice are restraints that Goodman recognizes”33 rather than it being right or wrong. Much of the popularity of Wright’s architecture was the consistency and coherence of his “style(s)” and the message they expressed regarding man’s habitation in the world.

In an article discussing contrast of the modern art era compared to the representational art of Caspar David Friedrich, Carter states “One outcome of these developments was the notion that the aim of art need not be narrating a story or copying nature, but rather to “express a state of feeling, an idea...or to create a harmony of colors and forms. This shift corresponds to the views of Cassirer, Langer, and Goodman that art is a means of expressing inner feelings or ideas and the forms, consciousness or unconscious that generates them”. Carter also quotes Kandinsky who stated that, “Our point of departure is the thought that the artist, in addition to the impressions he received form the external world, from nature, continuously collects experiences in an inner world,” and then Carter makes the connection of this to Hegel’s view “of a necessary perpetual spiritual progression away from dependence on the external world.” Compare this to what Wright said in Architectural Record in 1927, “Let us call Creative-Imagination the Man-light in Mankind to distinguish it from intellectual brilliance....A sentient quality...and to the extent that it takes concrete form in the human fabrications necessary or desirable to human life, it makes the fabrication live as a reflection of that Life any true Man loves as such—Spirit materialized.” This sounds similar to Hegel in the sense of an inner spirit animating exterior form; however, Wright’s sense of organic unity with nature seems to run contrary to Hegel’s idea of a spiritual progression away from the external world. Wright was aware of the Hegelian idea of art not being in nature when he wrote, “It has been said that ‘Art is Art precisely in that it is not Nature,’ but in ‘obiter dicta’ of that kind the Nature referred to is nature in its limited sense of material appearances as they lie about us and lie to us. Nature as I have used the word must be apprehended as the life-principle constructing and making appearances what they are...Nature inheres in all as reality. Appearances take form and character in infinite variety to our vision because of the natural inner working of this Nature-principle.” What seems obscure in Wright’s thought is how exactly he defines ‘Nature,’ but it clearly seems different from Hegel’s notion of the world. If Nature is not the external material appearance of things but a life-principle, then is that life-principle resident in man who thinks and creates or is it some other substance, be it of the world or some other source?

Wright, and the Japanese artists he wrote about, were seeking out the “hidden core of reality,” which implies that the artist is not presenting an entirely personal inner expression in his art along the lines of modern Western thought such as Kandinsky’s, but is an interpreter of some sort of the ‘life-principle’ animating the outward form of nature. This idea of finding something already there might also be seen in contrast to Goodman’s idea of worldmaking where worlds are made, not found. The modern Western artist was free to create without boundaries, unlike Wright’s vision of an artist whose “purpose is absolute beauty, inspired by the Japanese need of that precise expression of the beautiful, which is to him reality immeasurably more than the natural objects from which he wrested the secret of their being....Always we find the one line, the one arrangement that will exactly serve.”

That he saw in Japanese art a search for the underlying animating spirit or idea to nature is not surprising. The Japanese language contains many words that shed light on the many facets of their aesthetics. One of these words is ‘yugen,’ meaning a mystery and depth, “what lies beneath the surface; the subtle, as opposed to the obvious; the hint, as opposed to the statement.”40 Wright refers to the Japanese artist who by “the very slight means employed touches the soul of the subject so surely and intimately that while less would have failed of the intended effect, more would have been profane....so these drawings are all conventional patterns subtly geometrical, imbued at the same time with 41symbolic value, this symbolism honestly built upon a mathematical basis, as the woof of the weave is built upon the warp. It has little in common with the literal....Fleshly shade and materialistic shadow are unnecessary to it, for in itself it is no more than pure living sentiment.”42 Wright says a lot in the above quote, but defines little. One thing he is pointing out is that in his interpretation of the Japanese mindset there is a striving for the underlying ideal, which can be seen when they apply just the perfect line and harmony to achieve their desired effect. Elsewhere he states they are not looking for a literal or realistic representation in their art. He also states above that their drawings are ‘subtly geometrical’ and imbued with ‘symbolic value,’ a symbolism based upon an underlying mathematical structure. Others perhaps influenced Wright in deriving his idea of underlying mathematical and geometric structures; perhaps through Owen Jones, Arthur Dow, or even his early exposure to the Froebel block system. Whatever the source of that influence, he interpreted the Japanese aesthetic to have this structure as well. It seems his most direct reference to this in his writings is in reference to Hokusai’s Ryakuga Haya-oshie drawing textbooks which describe how forms can be broken down into geometrical elements of circles and squares and primitive elements43 Wright here and elsewhere when referring to symbolic value seems to place the symbolic value within the geometry underlying the form itself where he assigns certain meanings to platonic forms such as the square, circle, triangle, etc.

Again, while Wright is speaking in terms of the symbolic value and the meanings associated with those symbols, Nelson Goodman’s interest is in the overall structure of symbolic forms and not the value content of them which he states can vary according to world version and if coherent may be valid without being right or wrong.

CHAPTER FOUR: WRIGHT’S WORLDMAKING

So to Wright, the architect expresses properties of spirit through sensuous materials. These properties of spirit are expressed through symbolic forms with which the experienced and knowledgeable architect will work (as a musician his notes) to create meaningful forms—meaningful within a certain cultural context. Goodman described four modes of reference in his essay “How Buildings Mean.”44 These are denotation, exemplification, expression, and mediated reference. Applying Goodman’s modes of reference to the example of Unity Temple to see more specifically how Wright’s use of symbols set up his way of worldmaking, we could say that the mode of expression is in effect when Unity Temple is said to exhibit integrity. Wright thought there was an essential symbolic nature the square has, for example, that is different from the circle. His earlier work was based primarily on the square and rectangle, Unity Temple being one of his examples conceived as a symphony of the square, a cube in fact which he called “a noble form in masonry” and one expressing “Integrity.”45 When describing his approach to its design in his autobiography, he chose not to use the more literal denotative symbol of the traditional church steeple pointing to heaven but rather a design that expressed the “sense of inner rhythm deep planted in human sensibility [that] lives far above all other considerations in art.”46 The main cubical volume would become the “noble room for worship.”47 (fig. 1). Wright believed that the symbol of the square expressed integrity. Goodman defined expression as that which is metaphorically exemplified. Applying Goodman here does not give us a tool for determining the veracity of the association of the property integrity with Unity Temple, but rather that the architecture metaphorically exemplifies certain properties. A building expresses, according to Goodman, when it refers metaphorically and not with what it literally possesses48 (as is the case with exemplification).49 Unity Temple’s square forms and central space do not literally possess the trait of integrity or nobility but it expresses this immaterial concept through material form. Also, when Wright had made reference to the soul of the thing being brought out in architectural form much like the Japanese print through its idealism and simplification brought out the essence of its artistic expression, he was symbolically expressing thought metaphorically through physical form.

Unity Temple as conceived of by Wright also provides us a useful example of Goodman’s idea of exemplification. Goodman says, “exemplification is possession plus reference. To have without symbolizing is merely to possess, while to symbolize without having is to refer in some other way than by exemplifying.”50 Goodman contrasted denotation from exemplification stating that in denotation the reference runs from symbol to what it applies to as a label (a steeple refers to a church), but in exemplification the reference runs from labels or properties that refer back to and are possessed by the symbol (Squareness is a property referring to and possessed by Unity Temple).51 When clarifying the idea of exemplification, Goodman used the example of a sample or swatch, which refers to a certain aspect that is contained in the sample while not referring to all aspects of the sample (such as size). A swatch “exemplifies only those properties that it both has and refers to.”52 So just as a tailor’s swatch may refer to the texture and color but not the size and shape of the work, so too a building exemplifies a trait that it actually possesses. Capdevilla Werning defines this term when applying to architecture as follows: “A building can exemplify its form or that of some of its components and any feature related to form: geometrical shapes, planes, lines, horizontality, verticality, undulation, flatness, and so on....the Barcelona Pavilion exemplifies horizontality and the Seagram Building verticality and orthogonal geometry; Palladio’s Villa Rotunda exemplifies proportion...”53 In the design of Unity Temple Wright made primary motif of the square and celebrated this form in structure, plane, and space. We can say that Unity Temple exemplifies properties of the square and rectangular geometry, but it does not exemplify integrity since it does not possess the property of integrity, it refers to it metaphorically. However, Unity Temple both possesses properties of “squareness” and refers to squareness. Likewise, its cubical main sanctuary space exemplifies cubical centralized space. To take it one step further, Wright not only exemplified the square simply but he did so in a nested hierarchical composition of part-to-whole where the larger volume is reflected in the smallest detail and vice versa. For instance, the glass art in the skylights (fig. 2) follows a similar rectangular composition as the plan at large. It is neither the whole plan nor an exact replication of the floor plan, but it exemplifies certain aspects of the plan it possesses and refers to, such as the tartan grid geometry and rectangularity of form. Perhaps a result of Wright’s idea of the integrated whole is that exemplification often works bi-directionally in this architecture. Smaller detail elements refer to and exemplify larger elements, but also certain larger forms may exemplify smaller details also where certain but not all aspects are referred.

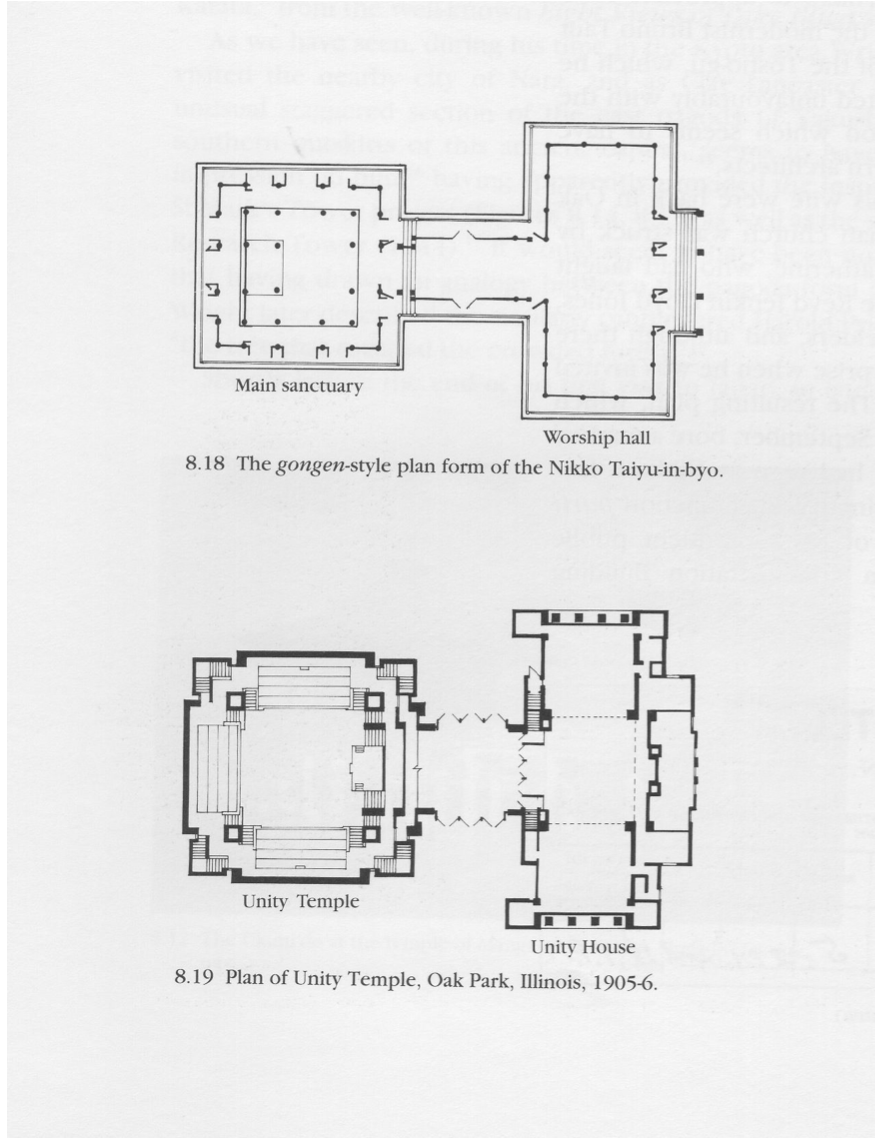

Completing our analysis of Unity Temple, Goodman describes two other modes of reference besides expression and exemplification, namely, denotation and mediated reference. Wright favored expression over denotation when he decided not to use a steeple or other traditional symbol denoting a church building. In fact, the cubical shape would have been confusing to the person who didn’t know what the use of the building was since it did not have any of the traditional symbols denoting the function of church. Mediated reference, or allusion, I feel is something that can be seen in this building. Besides the slatted screens that may be derivative from and thus allude to Japanese architecture, Kevin Nute points out a very strong precedent in the overall plan configuration between Unity Temple and the Japanese temple, Nikko Taiyu-in-byo.54 Unity Temple’s basic plan configuration, to one who knew Japanese temple layouts, would have another layer of meaning to them as they saw a mediated reference back to the Nikko Taiyu-byo temple. Mediated reference in

Frank Lloyd Wright, Unity Temple plan compared to Nikko Taiyu-in-byo. (Nute, pg 150)

this case, would be missing from one who did not have this prior knowledge. What is more interesting, however, is that Wright never admitted to designing this building with any Japanese architectural precedent in mind. If true, the mediated reference does is not negated but remains regardless of intention. Although Wright did not admit to this, the strong resemblance between the two plans is undeniable, and it would have been a building he was familiar with.55 (fig. 3) If the influence from the Japanese temple did influence Wright, then it is an additional example of Goodman’s worldmaking using deformation and recomposition of an existing version in order to produce Wright’s own version.

Goodman states that expression and exemplification (along with denotation and mediated reference) are symbolic reference functions and instruments of worldmaking.56 Additionally, for Goodman, a building is a work of art to the extent that it signifies, means, refers or symbolizes in some way, and its excellence is a matter of enlightenment, and as a work of art it can inform and reorganize our entire experience, give new insight, advance understanding, and participate in our continual remaking of a world.57 Unity Temple as a work of art fulfills Goodman’s methods above. It served to give new insight and reorganized one’s experience in various ways, including the unique ordering of the floor plan and sequence the congregant entered the sanctuary, the spatial ordering and proportions of the great meeting room, the way walls were used in defining this space, massive and yet letting light spill down from above. As Wright’s works often did, but even more so here, it created a total vision of architecture and man’s place in the world and serves as an example of Goodman’s worldmaking.

Susan Langer, like Goodman, also developed a theoretical structure for modes of representation that may shed some additional light on Wright’s organic form of composition. She offers a distinction between discursive versus presentational symbols. Whereas discursive symbols arrange elements (often words) in stable and context invariant forms and meanings, presentational symbols (often paintings or visual art) operate independently of fixed and stable meanings.58 Meaning here cannot be understood by taking parts in isolation but only in the context of their entire whole. Likewise, Wright’s organic architecture, the architecture of the integrated whole, must be understood in its wholeness rather than piecemeal since its ‘parts’ subordinate and deform themselves into the larger composition where their full effect is realized. In contrast to classical architecture for instance where there is more of an additive process of identifiable and complete parts (e.g. A symmetrical window with triangular pediment over it) compared to Wright’s organic architecture where the part may lose its own identity in service to the larger effect (e.g. An irregular corner window that conforms to wall or stone pier elements rather than establishing its own figural identity.) This would also lend credence to the thought that his buildings cannot be properly understood in an analysis of its parts in isolation but only through all the parts understood in their synthetic whole. This effect of the whole may be likened to an emergent property produced in the experience and understanding of the architecture. The meaning of an integrated whole is that relationships between elements determine meaning and not the elements in themselves, although individual elements may or may not have meaning in their own identity. But when an element, say an architectural element such as a window, or wall, is part of a total work of architecture, then a higher level meaning emerges based on the position of the element within the whole. So with Unity Temple the relationship of window to wall is unconventional as far as church architecture goes. Wright here lets the wall become a dominant element, rarely punctured within its boundary by a window, thus purifying the wall but also maximizing its quality in defining interior space. The windows are not treated so much as figural elements with individual identities as they are as negative space or slots between ends of walls or the tops of walls where they can march horizontally between pilasters, bringing light down from above the walls. The walls, as dominating as they are architecturally, especially on the exterior, yet derive additional meaning in their relationship and subordination to a higher element, the interior space of the great meeting room. Here, Wright famously quoted Lao-tzu that the essence of a room is not to be found in the walls or roof but in the empty void within.

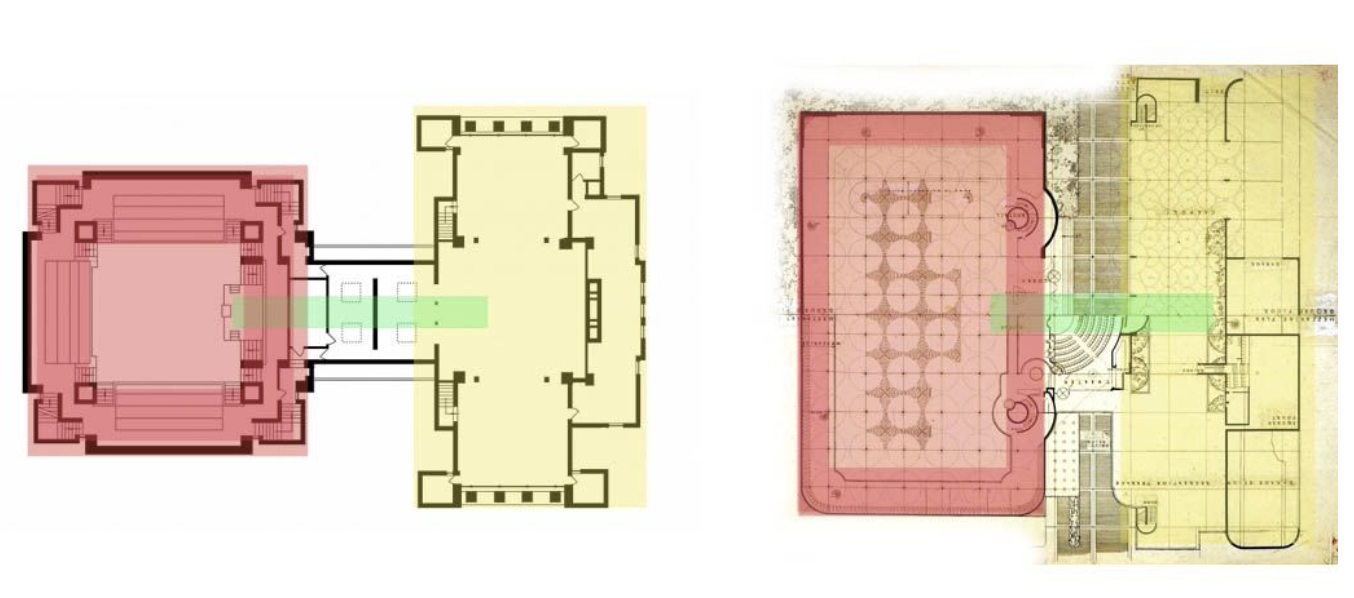

Another example from Wright’s oeuvre is the Johnson Wax administration building (see figures 4 & 5) designed roughly 30 years after Unity Temple. This building is instructive in that its relationship to Unity Temple highlights some of Goodman’s worldmaking ways. The building types were very different, one a church and the other a corporate headquarters. These two buildings, however, share a trait that most of Wright’s public buildings shared: an inward-focused central atrium type space. More than that, their plan typologies share common foundational characteristics. (fig. 6). If the influence of the Japanese temple Nikko Taiyu-in-byo mentioned above and claimed by Kevin Nute is true, then we can say also that the Johnson Administration building is progeny to the Japanese temple via Unity Temple. From figure 6 we can note several common organizing characteristics. There is a main centralized atrium-like space. In Unity Temple this is the main sanctuary space, in the Johnson Administration building this becomes the great workroom. In Unity Temple this space is a perfect square whereas in the administration building this space has been deformed into a rectangular space. However, both spaces are ringed by a peripheral upper floor or mezzanine and both have skylights above the central space. Also both buildings have a detached ‘service’ wing connected by a perpendicular circulation linkage. The Johnson Wax plan is very different from Unity Temple in many

5. Frank Lloyd Wright. Johnson Wax Administration Building, Great Workroom. Racine, WI.

24

ARCH991-Carter

2.) Frank Lloyd Wright. Unity Temple skylight art glass design:

ways; it is a much larger structure, the main space is filled with a field of dendriform columns whereas Unity Temple places four primary pier structures back at the corners. Unity Temple is hard-edged and formed of exposed concrete walls, columns, and roof. The administration building is soft, curved and has the additional texture of its red brick outside and inside. These reshapings from Unity Temple to the Johnson Wax administration building correspond to Goodman’s way of worldmaking called deformation. We may also consider Goodman’s Deletion and Supplementation way of worldmaking for some of the transformations. In deriving the administration building plan, Wright deleted many characteristics from Unity Temple such as the exposed concrete, heavy corner piers, etc. and supplemented it with curves, brick, unique dendriform columns, Pyrex horizontal tubing (instead of art glass), etc.

PART FIVE: WRIGHT’S INFLUENCE ON OTHERS

Goodman described the importance the frame of reference plays in ways of worldmaking and that these frames of reference “seem to belong less to what is described than to systems of description....We are confined to ways of describing whatever is described. Our universe, so to speak, consists of these ways rather than of a world or of worlds.”59 Frank Lloyd Wright provides us an example of worldmaking of striking influence. Over fifty years after his death, an industry has grown around his name and work, and his architecture has influenced and continues to influence architects around the world. Wright was a master of creating frames of reference that became the lens with which others perceived the world. These frames of reference were created by his words, his drawings, and his architecture. Through his words and his theories he painted a picture of an ideal world of design in harmony with nature. His renderings carefully edited out the insignificant and portrayed an idealized view of architecture in harmony with the landscape, much like the Japanese prints he emulated. These renderings were hardly realistic but intentionally framed to influence the eye to see architecture and nature in a certain way. His architecture carefully manipulated forms and spaces, indeed framing spaces to produce the visual experience and idea of compressed and limitless space he wanted you to see. If the measure of one’s ability to create ways of worldmaking is by creating a frame of reference by which others perceive and describe their world then we must recognize Wright as a significant worldmaker.

6. Frank Lloyd Wright, Unity Temple compared to Johnson Wax Administration Building